The following article has been reproduced from the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust’s Autumn/Winter 2019 edition of the ‘Antarctic Times’. Read on to learn how to subscribe to this biannual newsletter and become a ‘Friend of Antarctica’

Edward Bransfield

With many thanks to Michael Smith, writer and lecturer on Antarctic and Arctic exploration. Michael wrote about Edward Bransfield’s voyage in ‘Great Endeavour – Ireland’s Antarctic Explorers’ and his latest book is the first full biography of Sir Ernest Shackleton in a generation, ‘Shackleton – By Endurance We Conquer’.

History was made 200 years ago on 30 January 1820 when the mist and clouds parted in southern waters and a small band of sailors became the first humans to set eyes upon the mainland of the Antarctic Continent.

It was an historic discovery which proved the existence of the great southern continent and opened the era of Antarctic exploration, creating many legendary figures such as Ross and Crozier, Borchgrevink and Amundsen and Scott and Shackleton. Yet the person frequently overlooked from the cast of famous explorers who lifted the veil from the frozen continent is the man whose pioneering voyage in 1820 began the age of Antarctic exploration – Edward Bransfield.

Bransfield, an Irish-born 34-year old Ship’s Master in the Royal Navy, was commander of the sturdy little brig, Williams, that day in January 1820. However, Bransfield was an enigmatic figure, whose exploits were quickly forgotten and he died mostly unrecognised. No photograph or painting of Bransfield has ever been discovered, some of his important records were lost and he drifted to the margins of Antarctic history.

Remembering Edward Bransfield

Fortunately, the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust (UKAHT) has provided generous support to Remembering Edward Bransfield, a group of enthusiasts in Ireland chaired by Antarctic tour guide Jim Wilson, who are commemorating the voyage by erecting the first monument anywhere in the world to Bransfield.

UKAHT’s support for the Bransfield monument forms part of the Trust’s programme of commemorating past events and promoting the conservation, heritage and culture of Antarctica. In particular, the monument will help inform future generations about the significance of Bransfield’s pioneering voyage 200 years ago.

The monument will stand in Ballinacurra, the birthplace of Bransfield near Midleton in Cork with the unveiling taking place on Saturday 22 January 2019. You can learn more on the Remembering Edward Bransfield website.

In addition, a blue plaque will be unveiled at Bransfield’s former home at 11 Clifton Road, Brighton on 30 January 2020.

Early life

Bransfield’s own history is far from clear and helps explain why he remains such a mysterious figure. He was born in the small Irish community of Ballinacurra around 1785 and appears to have enjoyed a reasonable education. He probably worked on his father’s fishing vessel in the waters off the coast of Cork.

The peaceful life along Ireland’s southern coast came to an abrupt halt in 1803 with the outbreak of the Napoleonic War between Britain and France. In the search for able-bodied men, the brutal press gangs raided the Cork area and at 18-years old Bransfield was snatched. Bransfield, with his knowledge of the sea, was a good catch.

Although some 90,000 sailors were ultimately killed in the war, Bransfield somehow survived and rose slowly through the naval ranks. By 1812 he was appointed Ship’s Master and elected to remain in the Navy when the war ended with Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815. By 1819, Bransfield was stationed in Valparaiso, Chile, helping to protect British interests as the Chileans struggled for independence from Spain.

Discovering Antarctica

The first hint of the unexpected came in early 1819 when the merchant vessel Williams arrived with news of spotting unmapped islands while sailing around Cape Horn from Buenos Aires to Valparaiso. In keeping with protocol, Captain William Smith of the Williams reported the discovery to the naval authorities.

Initially the navy was not interested in Smith’s discoveries. On a return voyage around the Horn, Smith went in search of the uncharted land but emerged empty-handed. But in October 1819, during a further voyage to Valparaiso, Smith rediscovered the territory and made a brief landing on one island to claim the territory for King George III.

Smith, a 28-year old seaman and part-owner of Williams from the Northumberland colliery port of Blyth, had located what is today’s South Shetland Islands which lie to the north of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Rumours about Smith’s sighting spread quickly and the Navy was forced to act before rival American vessels descended on the area to exploit the hunting grounds for seals and whales. Captain William Shirreff, the senior naval officer in the area, immediately turned to Ship’s Master and navigator, Edward Bransfield.

Bransfield was given command of the 216-ton brig Williams – his first full command of a Navy vessel – and ordered to sail south to investigate, taking Smith and his crew to assist. Shirreff told the Admiralty that Bransfield was “well qualified” for the undertaking. Shirreff also ordered Bransfield to “conceal every discovery” made on the voyage.

Sailing alone into mostly uncharted waters without any support, Bransfield left Valparaiso in December 1819 with a year’s provisions and immediately ran into heavy seas. It took nine days to sail the first 6 miles and later blankets of fog, a common feature of the area, further hampered progress.

Bransfield sailed Williams along the chain of South Shetland Islands and took small party ashore on King George Island, the largest, for the ritual of formally claiming the new territory for the Empire. Williams then turned south into the unknown seas between the islands and the Antarctic Peninsula.

Today the 60-mile stretch of water is known as the Bransfield Strait and is the main thoroughfare for ships carrying tourists to the Peninsula.

Midshipman Charles Poynter wrote the only surviving record of the historic moment when the clouds opened on the afternoon of January 30 to reveal the panorama of the Peninsula’s mountains, glaciers and icefields. He wrote: “At 3 our notice was arrested by three very large icebergs and 20 minutes after we were unexpectedly astonished by the discovery of land SbW.” Poynter also wondered whether the party had found the “long contested existence of a Southern Continent.”

The main discovery was named Trinity Land after the maritime body, numerous islands were sighted and an imposing mountain was later called Mount Bransfield (2,500 ft). But troublesome fog and fears of running aground on the treacherous coast prevented Bransfield taking a landing party ashore.

Bransfield guided Williams along the coast in atrocious weather and finally sailed around the northern slopes of Elephant Island, where Shackleton’s party from Endurance would be marooned almost a century later. A brief landing was made on nearby Clarence Island before Williams was confronted with the impassable barrier of ice in the Weddell Sea. He recorded a “furthest south” of 64° 56’S and turned north for Valparaiso, which was reached in mid-April 1820.

Misfortunes?

Regrettably, Bransfield subsequently suffered a series of misfortunes. First some of his records, including the important logbook, were mislaid after being sent to the Admiralty, although some charts survived. Nor was the Admiralty particularly interested in his findings and Bransfield’s request to make a second voyage to the south was rejected. Bransfield later left the Navy and returned to the sea as a merchant mariner.

Further controversy arose over whether Bransfield or the Russian captain, Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen should be honoured as the person who discovered Antarctica.

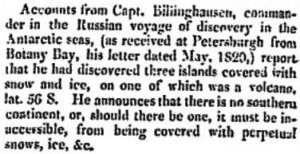

Bellingshausen had been in Antarctic waters at the same time as Bransfield. Three days before the Irishman’s sighting he reported seeing “continuous ice” and “ice mountains” as he sailed about 20 miles north of today’s Dronning Maud Land. Crucially, Bellingshausen made no record of sighting land and he never claimed to have found the continent. In newspaper interviews of the time, he said: “…there is no southern continent or should there be one, it must be inaccessible from being covered with perpetual snows, ice, etc.”

Bransfield’s case was supported by the 19th century French explorer, Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville who first named Mount Bransfield and explained: “This is why I named this mountain Bransfield, more to honour the memory of the only seaman who had been to these seas for science.” William Speirs Bruce conducted his own research into Bransfield a century later and concluded: “So, good old Ireland discovered the Antarctic Continent!”

More recently, the author Rip Bulkeley made an exhaustive study of the surviving papers from the Russian expedition and declared: “…Bellingshausen was not the first commander to see the Antarctic mainland…”.

By unhappy coincidence, the expeditions of both Bransfield and Bellingshausen failed to arouse much interest at home and some of his records went missing. Bellingshausen’s account of the expedition did not appear for 10 years and it was over a century later in 1945 before the first detailed English language version of the voyage was published. The original manuscript of Bellingshausen’s book, his expedition journals and the naval records of the expedition have all vanished.

Later life

In later life Bransfield drifted into obscurity and little is known about his movements. He married three times but does not appear to have produced any children. He settled on the south coast of England and maintained a close interest in seafaring, though he never wrote a book or published a diary about his exploits.

Edward Bransfield died a forgotten man in Brighton on 31 October 1852 at the age of 67. He outlived his rival Bellingshausen by nine months.

200 years on

Thanks to the support of the UKAHT and the local enthusiasts in Ireland, the monument in Ballinacurra will be a lasting memorial to the man who discovered the Antarctic Continent in 1820. More simply, the monument provides an opportunity to reassess his feats and allow Edward Bransfield to come in from the cold.

Become a ‘Friend of Antarctica’

The Antarctic Times is the biannual newsletter for members of the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust. For as little as £25 a year, you can become a ‘Friend of Antarctica’ with benefits including an annual subscription to the Antarctic Times, monthly email newsletters and invitations to select UKAHT and partner events. Find out more on the UKAHT website.