In the early 1800s the possibility that there might be a great southern continent had fascinated explorers and seafarers for centuries. The celebrated British explorer James Cook had nearly discovered Antarctica during his 1772-75 expedition. He sailed as far south as 71°10´ S, in one of the few places in the Southern Ocean where land cannot be seen. As a result, many presumed that such a continent might not exist.

This changed in February 1819.

First Sighting – February 1819

William Smith was a Master Mariner born in Seaton Sluice in Northumberland.

In the middle of January 1819, aboard his ship, Williams, he sailed from Buenos Aires, Argentina, bound for Valparaiso, Chile.

Williams, like many before and after her, found contrary winds in the Drake Passage on attempting to round Cape Horn. Unusually Smith decided to bare south and west in a higher latitude than usual.

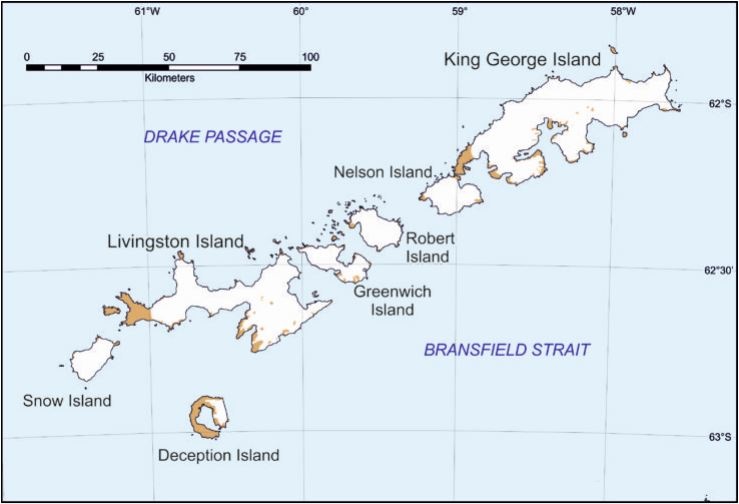

The result was that on 19 February 1819, William Smith and his crew were the first men to set eyes on what are now the South Shetland Islands, but which he initially called New South Britain. The exact location is uncertain but it was probably what is now Williams Point on Livingston Island. Smith did not linger in those uncharted ice covered waters and promptly departed the newly discovered islands.

He reported his discovery to the senior British naval officer of the Pacific coast of South America, Captain William Shirreff, when he reached Chile. Few believed Smith’s claims and “…all ridiculed the poor man for his fanciful credulity and his deceptive vision”.

First Landing – October 1819

However, Smith was not to be deterred. He tried to reach the islands again when he sailed back from Valparaiso in May of that year but failed due to severe ice concentrations.

By the time that Smith reached Montevideo, Uruguay, news of his discovery, and in particular, his observation of “a great abundance of whales and seals” had spread quite widely. He kept secret the exact details of his discovery and declined financial offerings to reveal the information.

Smith’s next voyage to Chile, during which he would again attempt to return to the islands, set off in September. This time he succeeded in relocating the islands and on the 16 October, he sent a small boat ashore at what is believed to be Esther Harbour on King George Island “where they planted a board with the Union Jack (sic), and an appropriate inscription, with three cheers, taking possession in the name of the King of Great Britain”.

The Consequences – Sealing

A further voyage of Smith aboard Williams was to follow the next year. This voyage included the first sighting of the Antarctic Peninsula. However, the secret of Smith’s discovery was already released. Sealing ships landed on the islands before the end of 1819 and were the precursors to well over a hundred sealing voyages there in the 1820s.

Smith’s achievement was little known, but significant. Yet his discovery was also a tragedy for the animals of the islands he discovered. As was already happening in nearby South Georgia, the seals of the South Shetland Islands were hunted to near extinction. It reached a point that within a few years the sealing industry in the region was already over, while in the next century the whaling industry, would wreak a similar devastation on the Southern Ocean’s whale population.

The history of human activity in what is now the Antarctic Treaty area is one largely of desolation of the continents biodiversity. It was 179 years later that humankind finally decided to protect rather than exploit Antarctica’s diverse, signing the Antarctic Treaty’s Protocol for Environmental Protection in early 1991.

Yet we should not blame Smith for the consequences of his discovery, but 200 years on recognise his achievement and celebrate him alongside his more famous contemporaries of Britain’s maritime exploration and the future heroes of the exploration of Antarctica.

More Information

Look out for further material related to the sighting of the first part of the British Antarctic Territory and continental Antarctica to be discovered throughout the year.

To learn more about the early exploration of the Southern Ocean you can read “Antarctica Observed” by A.G.E Jones or visit the Polar Gallery at the National Maritime Museum or the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge.